John Abraham’s Batla House is “Inspired by True Events”. Will it Acknowledge the Tough Questions Around the 2008 Encounter?

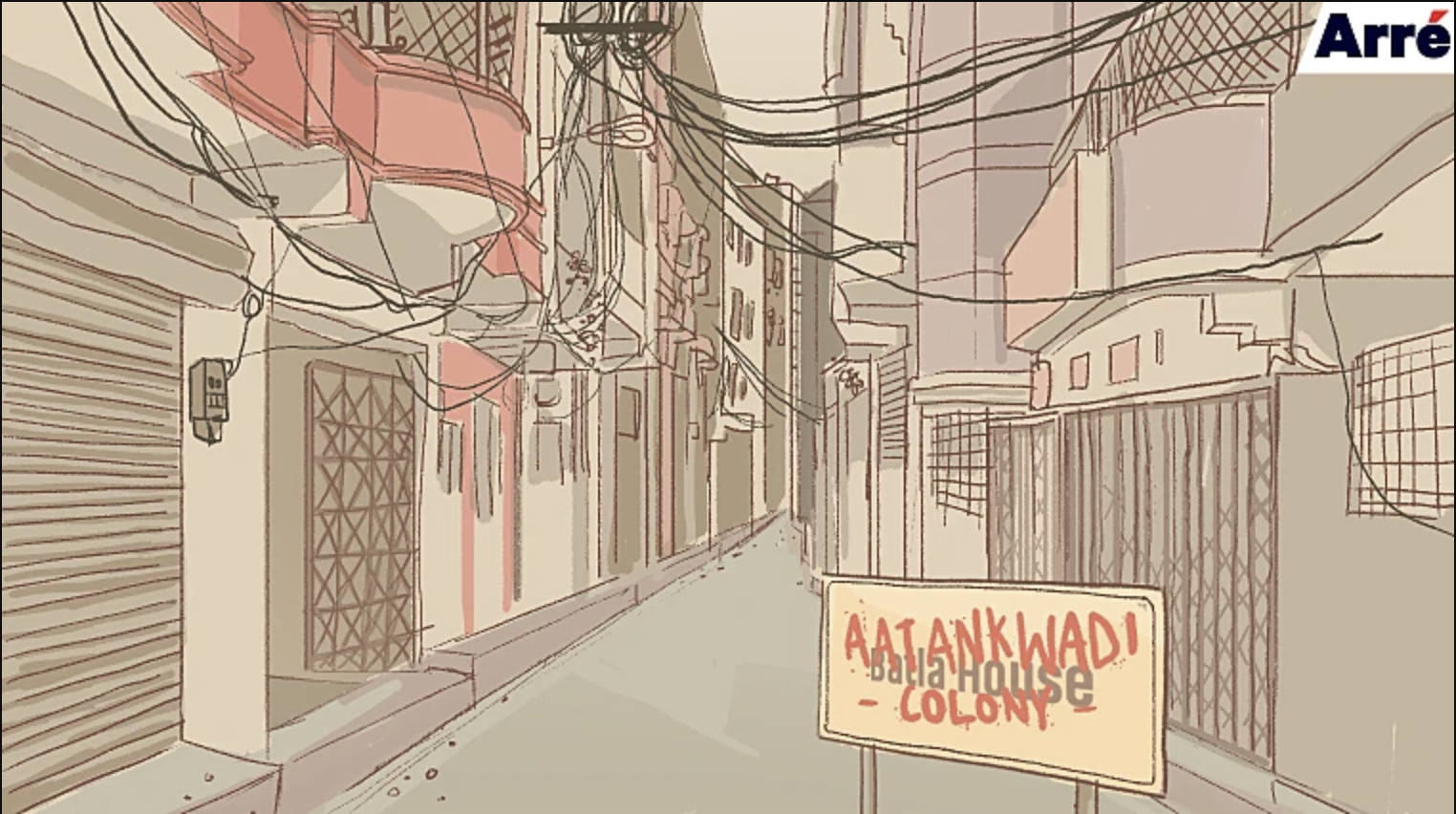

Illustration: Reynold Mascarenhas

John Abraham’s Batla House releases today. In the nationalism sweepstakes that several of our stars are currently engaged in, Abraham is still a challenger compared to Akshay Kumar, whose Mission Mangal is due to clash with Batla House at the box office. However, despite a petition seeking a stay on the film – by Ariz Khan and Shahzad Ahmed, two of the accused in events connected to the real-life Batla House case – the film will no doubt open to praise and paisa, unfettered by the fact that it is still one of the murkiest cases in the annals of Delhi Police’s speckled history.

I know this because I spent a fair bit of time reporting on the encounter in September 2008. Reporters are taught to follow stories – but many know that some stories follow you. The Batla House encounter, named for the killing of two alleged Indian Mujahideen terrorists by Delhi Police’s Special Cell from the neighbourhood, is the story that followed me.

***

Less than a week prior to the events of September 19, 2008, simultaneous blasts had gone off around Delhi, particularly in Connaught Place, the beating heart of Delhi, and Barakhamba Road, its pulsing vein. The Delhi incident followed the pattern of coordinated blasts in Jaipur, Bangalore, and Ahmedabad a few months earlier – and within minutes, Indian Mujahideen, the same terror outfit that had claimed responsibility for those bombings, added the capital to its list in an email sent to news channels. Delhi, certainly not the friendliest city in the world, felt even more serrated than usual. The police got to work, investigating leads wherever they could find them, including a few eyewitness accounts.

Early on September 19, there was news of the Delhi Police’s Special Cell conducting an encounter at Jamia Nagar’s Batla House neighbourhood. At L-18, a tall building in a rabbit warren of lanes, the police had tried to apprehend five alleged terrorists in a flat. Two of them, Atif Ameen (24), and Mohammed Sajid (17) were killed on the spot, while the Special Cell’s decorated officer who led the operation, MC Sharma, later succumbed to injuries sustained during the crossfire. Two of the men in the flat, Ariz Khan and Shahzad Ahmed escaped (but were arrested in subsequent years and are undergoing trial – they’re the ones appealing for a stay on the film). One, Mohammad Saif, surrendered. All of them were from Azamgarh. Almost all of them had a connection with Jamia University and school.

This, broadly, was the official version of events. The Special Cell argued that they were working on a tip-off, and had posed as salesmen, and that they didn’t think it would turn into a bloody encounter — but that the alleged terrorists had fired first and the police had had no option but to retaliate. To back that up, the police also stated that they had discovered arms and ammunition from the house.

Very few media outlets questioned the official version. Long before “fake news”, “paid media” and Godi media” became part of common parlance and Arnab Goswami was still preserving his vocal chords, several of the prime-time TV news channels and other media outfits were celebrating the Special Cell’s dubious “victory” and the killings of the “terrorists” – barely anyone used the terms “alleged” or “suspected”. It was as if their deaths were confirmation of their guilt.

Overnight, Batla House – and the predominantly Muslim Jamia Nagar, of which the colony is a part – acquired the label “Aatankvadi Colony”. I didn’t know it then, but the Batla House encounter marked a significant milestone along India’s deepening communal divide. A seething vein had been cut open. And it would sow the seeds of the rise of the kind of garbage peddled on mainstream news channels in the years to come.

As a fresh-faced cub reporter cutting her teeth on the features desk of a daily newspaper, I knew there was some agitation over the crime reporting team being biased or not asking tough questions, but it was too peripheral for me to care about.

Too peripheral, that is, until another senior colleague didn’t answer her calls on a Sunday. Two days after the encounter, halfway into my only weekly holiday, I received a frantic call from my boss, directing me to go to Batla House and “talk to the women there”. Several of the crime reporters, mostly young men, had been asked to leave the area by residents angered by the motivated coverage of the incident. I had no option but to set off, even with no prior experience of how to handle a sensitive case like this.

The few people in the neighbourhood whom I spoke to had no insight or inclination to talk about the incident, and unsurprisingly, I returned without a story. So in the next couple of days, I was dispatched once again to Jamia Nagar, and asked by my bosses not to return until I’d really really tried. My second attempt went almost as poorly as my first.

Overnight, Batla House – and the predominantly Muslim Jamia Nagar, of which the colony is a part – acquired the label “Aatankvadi Colony”.

A hard-boiled photographer colleague and I went up and down the floors of L-18 and several of its adjacent buildings, but residents would take a look at us, realise we were from the media even before we’d had a chance to introduce ourselves, and simply refuse to engage. If we were lucky, we might get an angry accusation out of them. On one particularly grave evening, we were nearly attacked by a mob of angry, mistrustful residents.

Finally, after two full days of this, we were exhausted and ready to call it quits. My bottle of water had run out, and I knocked on the door of a house diagonally opposite L-18, to ask for a refill before heading back to the newsroom. The door was opened by a woman in her late thirties… and just like that, the story’s complexion drastically changed. I was about to get an anonymous eyewitness account, one of the few published then, that would challenge the police’s version of the encounter.

***

For the next few hours, we spoke. The eyewitness – and at least a couple others came forward in the following days – had a vantage point to observe the goings-on: their toilet windows. Batla House was aware of heightened police activity in the area for about a week prior to September 19. On the day of the incident, the commotion started when a member of the Special Cell went up to the fourth floor, which drew the neighbours out into their balconies. Reacting to the commotion, the policemen waiting downstairs ran up, but none of them had their arms out, possibly because no one expected it to turn into a gunfight. Sharma yelled at the other residents to stay indoors because they could get hurt in the “firing”.

The eyewitnesses however, claimed that the Special Cell team had actually brought the two young men, Atif and Sajid, to the ground floor landing from their fourth-floor flat. There was a lot of shouting, and the two men appeared to be in a state of panic and unarmed at the time. The eyewitnesses heard the policemen hurling abuses at them. This was followed by gunshots.

Then, another commotion started after someone yelled, “Sahab ko goli lag gayi”, plausibly Sharma. After a gap of a few minutes, the eyewitnesses heard more gunshots, followed by a view of the policemen.

They were dragging the bodies of the two men upstairs.

Around the same time, Sharma was being led out of the building by two of his colleagues. The eyewitnesses could not ascertain the extent of Sharma’s injuries.

This version of events left more questions than answers. If the two young men and those who were apprehended were seasoned terrorists, why did they not flee the scene despite heightened surveillance? They must have also been aware of how the Special Cell was detaining and questioning people in the area, prior to September 19. And then, despite the bandobast, how did the remaining men in the flat manage their escape?

On one particularly grave evening, we were nearly attacked by a mob of angry, mistrustful residents.

Did Sharma – as the official line then was and continues to be – really remove his bulletproof jacket because it was too hot? Did the terrorists really shoot Sharma, or was it a ricocheting bullet? Conspiracy theorists had a field day with a photograph, shot minutes after the encounter and published in the Hindustan Times, that showed Sharma being helped along by two colleagues in plainclothes. He seems to have been shot in the upper arm. But his autopsy report revealed that he died of excessive bleeding after being shot in the arm and the abdomen. So when exactly was Sharma shot?

All of these are legitimate questions that continued to remain unanswered.

Meanwhile, a veil of secrecy descended upon the office. I was instructed to not breathe a word about the story or the eyewitness to anyone except my two editors. My reporter’s diary was kept under lock and key, in case we were called upon to produce it as evidence. I was asked not to discuss anything with my editors over the phone – every conversation related to the case had to be had in person and in private. In hindsight, we might have been erring on the side of caution, but we had some idea of who we were dealing with, the dreaded Special Cell. The elite unit, after all, has a notorious “take no prisoners” reputation.

***

In the weeks and months that followed, more and more questions began to surface. There were protests by some members of civil society like lawyer Prashant Bhushan, who would later represent the accused during the trial, and AIDWA member Kavita Krishnan. An NGO named Real Cause occasioned a National Human Rights Commission inquiry, which went on to give a clean chit to the Delhi Police in 2009. (However, many of the residents I spoke to in subsequent days, stated that the Commission had not visited the area or questioned them.) The Jamia Teachers’ Solidarity Association, particularly, set up a sustained campaign: They organised Jan Sunwais (public hearings) and kept a count of all the men – some of them juveniles – who were picked up on suspicion and illegally detained.

Did Sharma – as the official line then was and continues to be – really remove his bulletproof jacket because it was too hot?

It also went unexplained why the “dreaded terrorists” cited their actual addresses in their tenant verification forms and purchase of SIM cards – addresses that the police would later go on to raid. Then, two years later, RTI activist and journalist Afroz Alam Sahil was able to obtain the post-mortem reports of the men killed in the encounter. Unlike the Special Cell’s claims of a filmy shootout, the bodies of the alleged terrorists bore trauma injury marks on their backs, suggesting assault – and squaring up with our eyewitness accounts. The bullet injuries on the head of Sajid, the minor killed in the encounter who was supposed to have fired upon Sharma, appeared to have a top-down trajectory suggesting that he was shot at close range.

The sea of questions swelled during the trial of Shahzad Ahmed – one of the two who had escaped the scene but was apprehended in Azamgarh two years later – and was accused of shooting Sharma. The police failed to produce any independent witnesses in the case, the court failed to acknowledge Ahmed’s claims of a forced confession, and even ignored the statement of the surrendered “terrorist”, Mohammed Saif, that Ahmed was not even present in the flat. In 2013, he was convicted and sentenced to life.

***

In my time at the publication, I continued to follow the case for a couple more years. I tried desperately to get in touch with their families, but they’d either been advised against speaking to a largely hostile media, or the fight had gone out of them. Eleven years on, we have Batla House. The only thing I am surprised by is how long it took Bollywood to touch the subject.

In a bog-standard cop movie trailer, by which I mean it is the perfect Independence Day vehicle, the slain men have already been labelled terrorists, echoing they way they were condemned by a compliant media a decade ago. This is evident from a slate that announces this is a film, “inspired by true events labelled as untrue”. Abraham portrays Special Cell DCP Sanjeev Kumar Yadav, and is being pitched as a wronged hero whose redemption will no doubt form the crux of the storyline.

I wonder if any of the questions, doubts, and conjectures that loomed over the actual Batla House incident will be addressed by the film. Abraham had tweeted when the trailer had released: “Was the nation prejudiced or was it really a fake encounter? The questions will finally be answered.” But from what I can make out from the trailer – and given what I know of Bollywood encounter films – the film seems to have made up its mind which side of the narrative it is interested in portraying.